Introduction: The Double-Spending Problem

When you develop E-commerce platforms, you may commonly face a coordination problem: refunds, for example, can be triggered simultaneously by customers, sellers, or automated fraud detection systems. Without proper distributed coordination, the same order gets refunded multiple times.

Consider a real-world scenario: an order with a total value of $200 receives three concurrent $200 partial refund requests within a 1-second window.

- The Customer requests a $200 refund for a damaged item via the app.

- The Seller initiates a $200 courtesy refund due to a shipping delay.

- The Loyalty System triggers an automated $200 refund as part of a promotional price-match guarantee.

Three separate microservices process these requests simultaneously. Each service reads the order state from the database, seeing a “remaining refundable balance” of $1,000. Because the requests overlap before the database can update the balance, all three services validate the transaction as “safe.”

The Result: Instead of the intended $200 reduction, the system processes three distinct transactions. The customer receives $600 in total refunds, and the remaining “real” order balance drops to -$400, despite only one $200 deduction being legitimate in the context of the user’s intent. This race condition leads to a $400 unintended loss due to a lack of distributed locking or atomic counters.

Robust safeguards are also essential to defend against potential external malicious attacks.

Why Traditional Locks Don’t Work

Wrapping the refund logic in a synchronized block seems like a natural solution:

// Anti-pattern: only locks within a single JVM

synchronized(this) {

if (!order.isRefunded()) {

processRefund(order); // Calls payment gateway API, updates order status

}

}

Otherwise, you may use mutex if you are using different programming langaugase. This works on a single server, but modern architectures run stateless microservices across multiple instances. Request A hits server-1, Request B hits server-2, Request C hits server-3. Each JVM has its own heap and its own synchronized locks that only coordinate threads within that process. Local mutexes can’t coordinate across network boundaries.

Timing Issues

In addition to local locking problem, timing issues still cause race conditions:

Network delays: Request A starts at T=0ms but takes 150ms to reach the database due to network jitter. Request B starts at T=50ms, arrives first, and commits.

Stale reads: Request A updates the order status to “refunded” in the primary database. Request B reads from a replica that hasn’t caught up yet and sees “not refunded.”

Traditional concurrency primitives—mutexes, semaphores, synchronized blocks—assume shared memory. Distributed systems have shared nothing except the network, which is unreliable by nature.

The Core Problem

This is the double-spending problem in distributed systems: operations that must execute exactly once (like issuing a refund) execute multiple times due to coordination failures. If the refund operation is not idempotent—running it twice calls the payment gateway twice, creating two separate refund transactions and doubling the loss. Idempotency is a property of an operation where performing it multiple times has the same effect as performing it once. In distributed systems, a client might retry a request due to a network timeout, leading to the same command being sent twice. A distributed lock, often used with a unique idempotency key, ensures that even if these duplicate requests arrive simultaneously, only the first one is executed while subsequent ones are recognized as repeats and safely ignored.What is Idempotency?

Solutions include database-level uniqueness constraints (optimistic locking), distributed locks (Redis, ZooKeeper), and idempotency keys for deduplication at the API layer. Database constraints provide atomic enforcement at the data layer. Distributed locks coordinate across services but require careful handling of timeouts and failures. Idempotency keys prevent duplicate API requests from causing duplicate operations. Each approach has different consistency guarantees and trade-offs.

When Do We Actually Need Distributed Locks?

Modern backend systems run multiple stateless instances for scalability and fault tolerance. When these instances need to coordinate actions on shared state, that coordination must happen externally—typically through distributed locks.

Shared Resources

Multiple processes competing for limited resources need coordination to prevent conflicts.

External API quotas are a common example. You’re paying for an API that allows 100 requests per minute across your entire infrastructure. Without coordination, each of your 10 server instances might send 100 requests, hitting 1000 requests and either getting throttled or paying overage fees.

Leader election for background job schedulers presents another case. If you have 5 instances but only one should run scheduled jobs, distributed locks ensure only one instance becomes the leader and executes those jobs.

Efficiency: Avoiding Redundant Work

Some operations are expensive enough that running them multiple times wastes significant resources.

Consider a system that generates daily analytics reports taking 5 minutes and consuming substantial CPU. If 5 instances all start this job simultaneously, you’ve wasted 20 minutes of compute time and potentially created inconsistent results. A distributed lock ensures only one instance performs the work while others skip it or wait for the result.

Hot key expiration occurs when a single, highly popular cache key expires while 1,000 requests hit your API for that same data within milliseconds. Without a lock, all 1,000 concurrent requests will find the cache empty and simultaneously trigger the same expensive database query. A distributed lock ensures only the first request is granted the right to rebuild the cache, while others wait briefly to read the newly updated value, preventing a massive spike in database load.

Correctness: Preventing Data Corruption

This is where distributed locks coordinate at the application level, before you even start database transactions.

While idempotency logic (like checking a unique key) prevents duplicate records, a distributed lock prevents race conditions within that check. Without a lock, two simultaneous requests (e.g., a user double-clicking “Refund”) might both pass the “is this already processed?” check at the same microsecond. A distributed lock on the idempotency key ensures that only one request can evaluate the state and initiate the transaction.

In complex workflows involving external systems—such as provisioning a user account across a Database, Auth Provider, and SaaS tool—a database transaction alone cannot roll back external side effects. By locking the User ID at the start, you ensure that concurrent requests don’t create “zombie” accounts or redundant resources across third-party providers. These defensive mechanisms serve as essential security measures to protect the system from malicious external exploits, such as race condition attacks.

Why External State Management?

Stateless servers can’t coordinate among themselves—they have no shared memory. A lock held in one process’s memory is invisible to other processes or servers. You need a system that all instances can access for coordination: Redis, a database with proper transaction isolation, etcd, or a consensus system like ZooKeeper.

The trade-off is clear: you gain coordination across instances but introduce a dependency that every lock operation must contact. If your lock service is slow or unavailable, it blocks all operations requiring coordination.

Solution: Redis for Simple & Performance-First Locking

Redis is the simplest way to implement distributed locks. Its single-threaded execution model and atomic operations handle the core concurrency challenges.

Why Redis Works Well

Redis’s single-threaded execution processes commands sequentially. When you execute SET key value NX, Redis checks for existence and sets the key atomically—no other command can run between these steps. This eliminates the race conditions you’d face trying to implement “check-then-set” logic at the application level.

Redis operations are fast (sub-millisecond on the server), though in distributed systems, network latency typically dominates (1-10ms+ depending on your infrastructure). Still faster than database row locking, and you don’t need to manage transaction isolation levels or worry about deadlocks across different tables.

Implementation

The core Redis command:

SET invoice:123 550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000 NX PX 30000

Breaking this down:

invoice:123- your lock key550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000- unique token (UUID) identifying this lock holderNX- only set if key doesn’t exist (this is your lock acquisition)PX 30000- expire after 30 seconds (your safety mechanism, TTL)

The unique token is critical. Without it, Service A could accidentally release Service B’s lock. When releasing, you must verify you still own the lock:

import uuid

import redis

import time

redis_client = redis.Redis(host='localhost', port=6379, decode_responses=True)

def acquire_lock_with_retry(lock_name, acquire_timeout=10):

lock_id = str(uuid.uuid4())

end_time = time.time() + acquire_timeout

while time.time() < end_time:

# NX: key가 없을 때만 획득 시도

# PX 30000: 30초 후 자동 만료 (Safety mechanism)

if redis_client.set(lock_name, lock_id, nx=True, px=30000):

return lock_id

# 획득 실패 시 짧게 대기 (CPU 부하 방지)

time.sleep(0.1)

return None

# 실행

lock_key = 'invoice:123'

lock_id = acquire_lock_with_retry(lock_key)

if lock_id:

try:

# Process invoice

pass

finally:

# Release only if we still own the lock (Lua script ensures atomicity)

release_script = """

if redis.call("get", KEYS[1]) == ARGV[1] then

return redis.call("del", KEYS[1])

else

return 0

end

"""

redis_client.eval(release_script, 1, lock_key, lock_id)

Most Redis client libraries provide higher-level abstractions(aioredis too):

# redis-py convenience wrapper

lock = redis_client.lock("invoice:123", timeout=30)

if lock.acquire(blocking=False):

try:

# Process invoice

pass

finally:

lock.release()

The library handles the unique token internally.

Handle Microservice Crashes

Always set a TTL on your locks. If a service acquires a lock then crashes, the TTL ensures Redis automatically releases it.

Set TTL to 2-3x your expected processing time. If your invoice processing takes 5 seconds at P99 latency, use a 15-second TTL. Monitor your production metrics—if you see locks expiring before release() is called, either processing is taking too long or services are crashing.

Advanced Tips

To move from a basic implementation to a production-grade locking system, consider these two optimizations:

Use Pub/Sub to Reduce Overhead: The “polling” method (using time.sleep()) creates unnecessary network traffic and CPU load. In a high-concurrency environment, thousands of retries can overwhelm Redis. Instead, use Redis Pub/Sub. When a service fails to acquire a lock, it subscribes to a channel for that lock. When the current holder releases the lock, it publishes a message to the channel, signaling waiting clients to try again. This transforms a “busy-wait” into an efficient, event-driven process.

Ensure Atomicity with Lua Scripts: You might wonder: If Redis is single-threaded, aren’t all operations already atomic? While Redis executes individual commands sequentially, a sequence of multiple commands (like GET then DEL) is not atomic. Between your GET and DEL commands, Redis could process a command from another client, leading to race conditions—such as accidentally deleting a lock that has already expired and been re-acquired by someone else. By wrapping your logic in a Lua script, you ensure the entire “check-then-delete” sequence is treated as a single, uninterrupted operation.

Instead of sending the full script, you simply send the SHA1 hash using EVALSHA. Redis then executes the script it already has in its cache.

# Lua Script: Attempt to acquire or refresh a lock

acquire_lua = """

if (redis.call('exists', KEYS[1]) == 0) or (redis.call('get', KEYS[1]) == ARGV[1]) then

redis.call('set', KEYS[1], ARGV[1], 'px', ARGV[2])

return 1

else

return 0

end

"""

acquire_sha = redis_client.script_load(acquire_lua)

def acquire_lock(name, token, timeout_ms):

# Returns 1 if successful, 0 otherwise

return redis_client.evalsha(acquire_sha, 1, name, token, timeout_ms)

# Lua Script: Release the lock only if the token matches

release_lua = """

if redis.call("get", KEYS[1]) == ARGV[1] then

return redis.call("del", KEYS[1])

else

return 0

end

"""

release_sha = redis_client.script_load(release_lua)

def release_lock(name, token):

return redis_client.evalsha(release_sha, 1, name, token)

Licensing Note

If you’re starting fresh, consider Valkey—a Linux Foundation fork maintaining Redis’s BSD license after Redis changed to restrictive licensing in 2024. It’s protocol-compatible with all Redis clients.

The Trade-off

Redis locking is fast and simple, but introduces a single point of failure. If Redis goes down, no service can acquire locks. For many use cases this risk is acceptable, but if you need true fault tolerance, you’ll need a different approach.

Distributed Solutions: Stability & Coordination

When single-node Redis fails, all locks are lost. Distributed alternatives eliminate this single point of failure, but each comes with its own trade-offs.

Redis Family

While leveraging your existing Redis infrastructure for distributed locking may seem like a charming, low-cost option with minimal migration overhead, it introduces a dangerous trade-off between availability and safety. The core of the issue lies in the fact that Redis replicationis inherently asynchronous.

The Asynchronous Replication Gap Redis replication is asynchronous. When a client acquires a lock, the write happens on the Primary node first. The Primary sends an acknowledgment to the client before the data is synchronized with the Replicas.

The Scenario:

- Client A successfully acquires a lock on the Primary.

- The Primary acknowledges the lock but crashes before replicating the key to its Replicas.

- A Replica is promoted to Primary via failover (Sentinel or Cluster).

- The new Primary has no record of the lock held by Client A.

- Client B requests the same lock, and the new Primary grants it.

The Result: Both Client A and Client B now hold the “exclusive” lock simultaneously, leading to race conditions and potential data corruption.

The Clock Drift Issue: Redis locks rely on TTLs (Time-to-Live). In a distributed environment, if the system clocks between the Primary and Replica (or between different clients) are not perfectly synchronized, a lock might expire prematurely on one node while being considered valid on another, further complicating the reliability of the lock during a failover.

Redis Sentinel provides high availability through automatic failover. It runs multiple Redis instances (one master, multiple replicas) with Sentinel processes monitoring them. When the master fails, Sentinels elect a new master from the replicas.It does not alter the underlying asynchronous replication mechanism of Redis. You still write to a single master at a time—it’s not truly distributed, just fault-tolerant, sharing the same essential vulernability.

Redis Cluster partitions data across multiple masters using hash slots (16,384 slots total). Each key is hashed to a slot, and each master owns a range of slots. This gives you horizontal scalability and removes the single-master bottleneck.

- Still has asynchronous replication — you can lose locks during failover.

- Network overhead increases: nodes gossip to discover cluster membership, and clients must redirect requests when they hit the wrong slot owner.

- More complex operations (multi-key transactions) don’t work across different slots unless you use hash tags (

{user123}:lock,{user123}:dataland on the same node).

Redlock might be a possible alternatives.

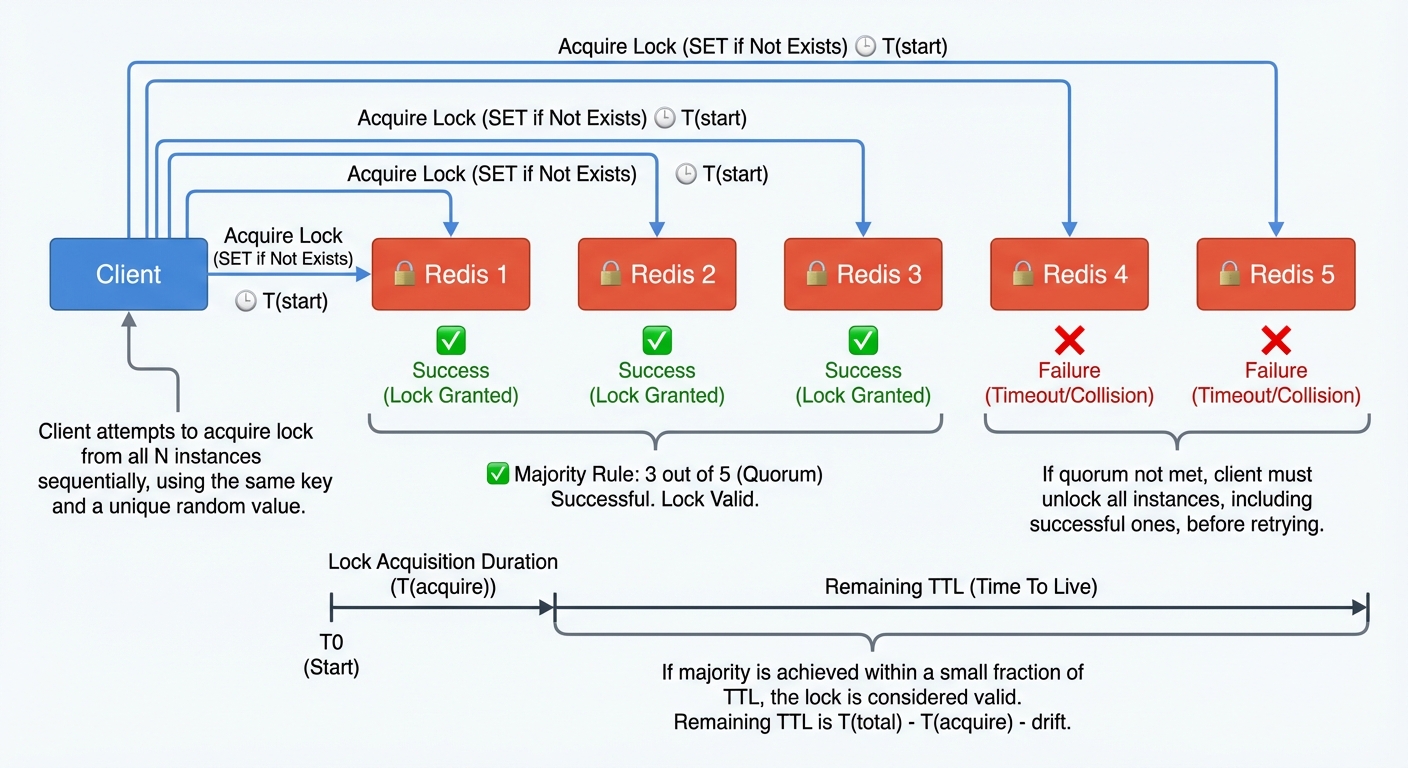

Figure: Redlock algorithm - Client must acquire locks from majority of independent Redis nodes

Figure: Redlock algorithm - Client must acquire locks from majority of independent Redis nodes

To address the vulnerabilities of asynchronous replication, the creator of Redis proposed the Redlock algorithm. Instead of relying on a single Primary node, Redlock uses multiple independent Redis instances (typically five) that do not replicate to each other.The logic is as follows:A client attempts to acquire the lock from all $N$ instances concurrently.The lock is considered acquired only if the client succeeds in reaching a majority (e.g., 3 out of 5 nodes) within a timeframe significantly shorter than the lock’s TTL.The effective validity time of the lock is the original TTL minus the time spent acquiring it.While Redlock mitigates the “lost write” issue during a failover, it is still not a silver bullet, since it still suffers from clock drift issue. If you’re interested in the deep architectural debate surrounding this issue, I recommend checking out Martin Kleppmann’s article: How to do distributed locking.

Wrap Up: At its core, the Redis family was architected as a high-performance, key-value data store designed for speed and availability. While it excels as a caching layer, it was never built to serve as a CP (Consistent and Partition-tolerant) system required for reliable distributed locking. Moreover, all options still rely on TTL-based expiry and asynchronous replication, which are inherently “lossy” during failovers by their nature. Adopting one of these approaches may leave you wrestling for days with elusive bugs that are notoriously difficult to trace and reproduce.

Zookeeper: Built for Coordination

Apache Zookeeper was designed specifically for distributed coordination tasks—leader election, configuration management, and distributed locks. Unlike Redis (a cache that grew locking features), Zookeeper’s core data model is built around coordination primitives.

Breif Internals

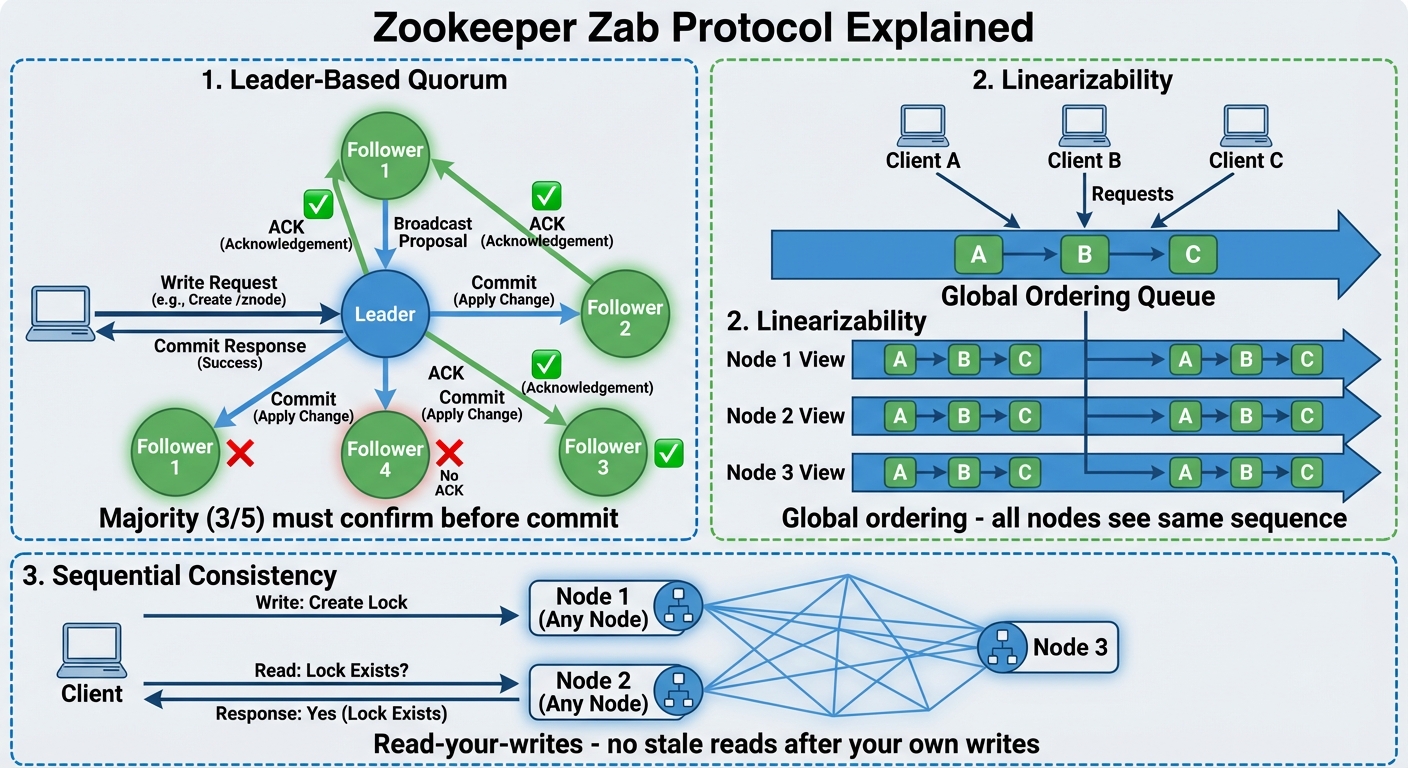

Zookeeper’s reliability stems from its core consensus engine, Zab (Zookeeper Atomic Broadcast). Unlike the simple “fire-and-forget” replication found in Redis, Zab ensures that every change—such as acquiring or releasing a lock—is a collective decision made by the cluster.

The Power of the Majority (Quorum): Zookeeper operates on a “majority rule” system. When a client requests a lock, the Leader node doesn’t just say “yes” immediately. It broadcasts the request to the other nodes and waits for a quorum (a majority) to acknowledge and log the write.

The Safety Net: Because a majority must agree before a lock is confirmed, the system ensures that even if the Leader crashes, the new Leader elected from the survivors will always possess the most recent, confirmed lock state.

Guaranteed Order (Linearizability): In a distributed environment, the order of events is everything. Zab enforces linearizability, meaning every single update is processed in a strict, global order.

The Result: Every node in the cluster sees the exact same timeline of events. You will never encounter a “split-brain” scenario where different nodes disagree on who acquired the lock first.

The Art of Handling Lag When first diving into Zookeeper, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that all nodes are perfectly synchronized at every moment. In reality, like any distributed system, a Follower node might briefly serve “stale” data due to network lag. However, Zookeeper is designed so that momentary lag never compromises safety. It handles this through a clever combination of Eventual Consistency and strict ordering.

Zookeeper provides a sync() command that forces a Follower to catch up with the Leader’s latest state before performing a read. While sync() provides absolute linearizability, it is operationally “heavy” because it requires an extra round-trip to the Leader. Thus, most production-grade lock implementations avoid constant sync() calls. Instead, they rely on the Watcher mechanism and a re-validation loop to cover the lag.

Zookeeper provides another critical guarantee: A watch event is promised to arrive at the client before it sees any data change. When the previous lock holder disappears, the Leader broadcasts this deletion. Each Zookeeper node ensures it sends the “Deleted” notification to its connected clients before it updates its own local database. By the time a waiting client receives the alert and re-reads the child list, the latest status is likely to be reflected. Let’s discuss this further in the following section.

How To Use For Distributed Locking

Zookeeper uses a hierarchical namespace similar to a filesystem. Each node (called a znode) can store small amounts of data (~1MB max, but typically a few bytes for locks). For locking, you create ephemeral sequential znodes:

Ephemeral znodes disappear when the client connection drops—solving the dead client problem cleanly. Instead of relying on a TTL, Zookeeper ties a lock’s life to the client’s live session.

Moreover, in a basic lock model, multiple servers compete in a “race” where the fastest network usually wins. This can lead to Lock Starvation, where some servers never get a turn. Zookeeper solves this by assigning a sequential number to every lock request(lock-001, lock-002). Only the client with the lowest number holds the lock, thus ensuring every process is served in the exact order it arrived.

Let’s see how watch works with ephemeral node with example code below.

# Zookeeper lock pattern

zk.create("/locks/my-resource/lock-", ephemeral=True, sequence=True)

# Creates: /locks/my-resource/lock-005

while True:

# 1. Fetch all participants (this might return a slightly stale list due to lag)

children = zk.get_children("/locks/my-resource")

children.sort()

# 2. Check if I am the owner (lowest sequence number)

if children[0] == my_lock_node:

# [SUCCESS] Confirmed as the leader

perform_critical_section()

zk.delete(my_lock_node) # Release lock

break

else:

# [WAIT] Watch the node immediately preceding mine

# This blocks until the previous node is deleted or the session drops

wait_for_event(watch_previous_node(children[children.index(my_lock_node) - 1]))

# Once the event fires, the loop restarts to re-validate the state

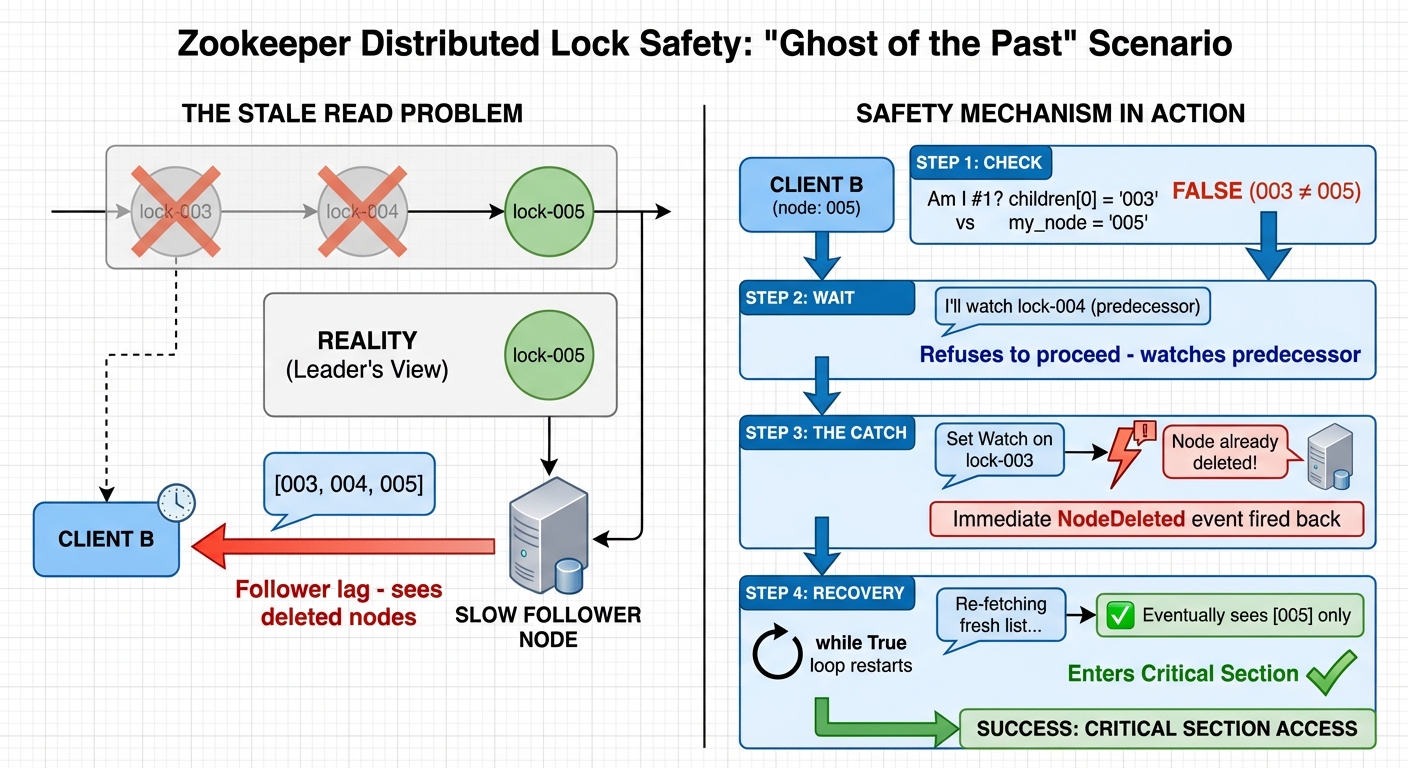

Consider a extreme case, which are almost impossible to happen. A “Ghost of the Past” scenario to undestand zookeeper’s safety.

- Client B successfully created 005.

- But the Follower node it’s reading from is so slow that it still shows 003 as the head of the list.

- In reality, 003 and 004 have already finished their work and deleted their nodes right after 005 is created, but the Follower doesn’t know that yet.

When the code executes, it follows a strict path to safety:

- Step 1 (Check): The client compares the head of the list (003) with its own node (005). The condition if children[0] == “lock-005” returns False.

- Step 2 (Wait): Because it is not #1, Client B refuses to enter the critical section. Instead, it prepares to watch the preceding node (003). – Step 3 (The Catch): As Client B attempts to set a Watch on lock-003, the Zookeeper server realizes the node is already gone. It immediately fires a “Node Deleted” event back to the client.

- Step 4 (Recovery): This event wakes Client B up instantly. The while True loop restarts, the client re-fetches the list, and it continues this cycle until the lag clears and it sees itself at the front of the line.

Real-world usage

Kafka used Zookeeper for broker metadata until v2.8, when scalability issues with large clusters led to the KRaft replacement.

What to watch for:

- Zookeeper is operationally complex. Running a stable 3-5 node ensemble requires tuning and monitoring.

- Not designed for high-throughput data storage. Write-heavy workloads can stress the system.

- Clients must handle connection loss and session expiration explicitly. Session timeout configuration directly impacts lock safety.

Apache Ignite: Distributed Data Grid

Apache Ignite is a distributed in-memory data grid with strong consistency. Unlike Redis (single-threaded per core) or Zookeeper (coordination-focused), Ignite is built to handle massive transactional workloads across a distributed cluster.

Data Structure

Ignite has serveral mechanisms to handle massive workloads in parallel.

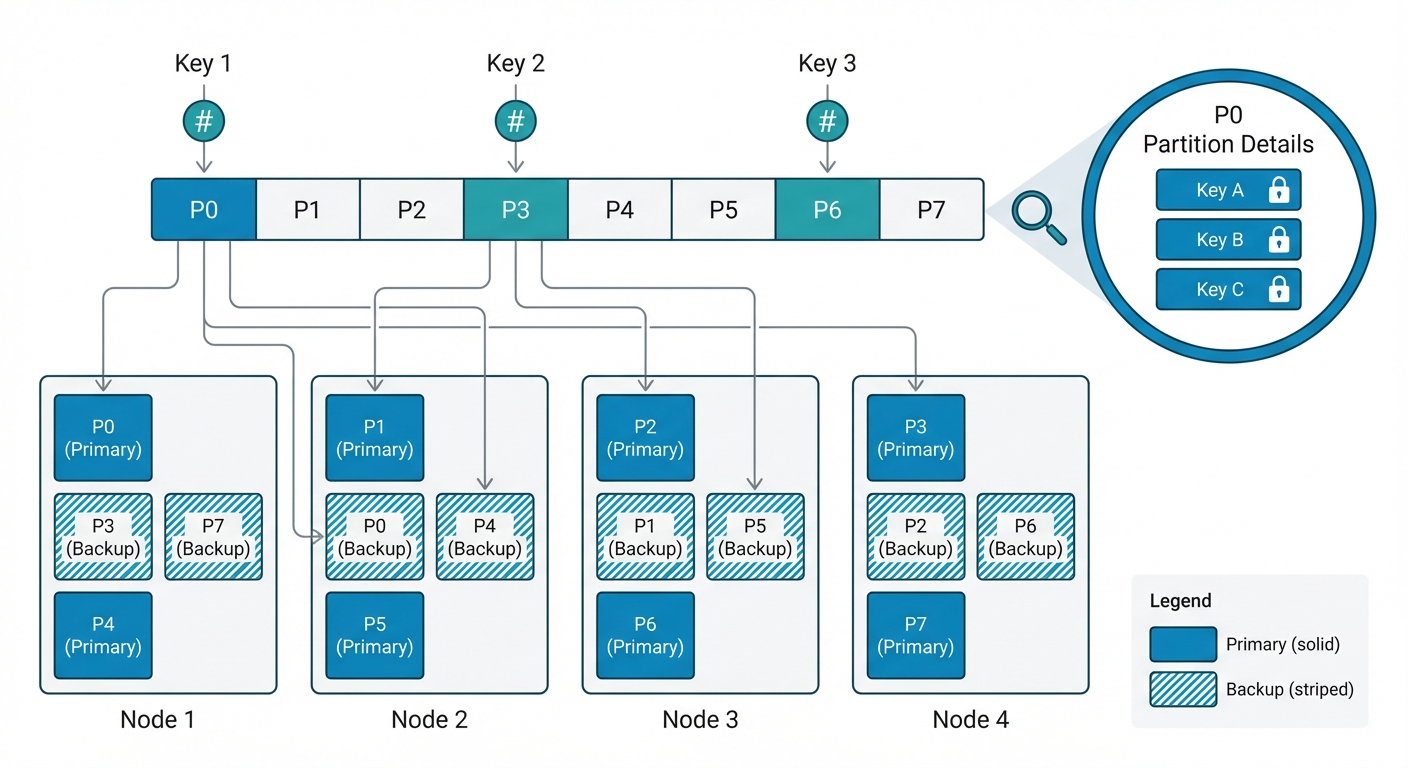

Figure: Ignite’s hash-partitioned data distribution with backup replicas and key-level locking

Figure: Ignite’s hash-partitioned data distribution with backup replicas and key-level locking

Beyond the Leader Bottleneck: Hash-Based Partitioning The secret to Ignite’s throughput lies in its Shared-nothing Architecture. While ZooKeeper forces every lock request through a single Leader node, Ignite distributes data and its management across the entire cluster.

- Hash-Partitioning: Every data (Key) is mapped to a specific partition using a deterministic hash function. These partitions are spread across all nodes in the cluster.

- Decentralized Control: The node that owns the primary partition for a specific key acts as the “mini-leader” for that key. This means every node in the cluster simultaneously acts as a coordinator for different subsets of data.

Fine-Grained Concurrency: Key-Level Locking In Ignite, the locking granularity is at the individual Key level, not the Partition level.

- Parallelism within Partitions: Even if thousands of transactions land on the same partition, multiple “write” operations can proceed concurrently and in parallel as long as they are targeting different Keys.

- Multi-Threaded Processing (Striped Thread Pool): Each Ignite node utilizes a sophisticated multi-threading model. Incoming requests are processed by a pool of worker threads, allowing a single node to saturate all its CPU cores to handle thousands of concurrent lock acquisitions.

ACID Transactions

Ignite supports full ACID transactions across distributed data. Locks can be held within transaction scope or until commit:

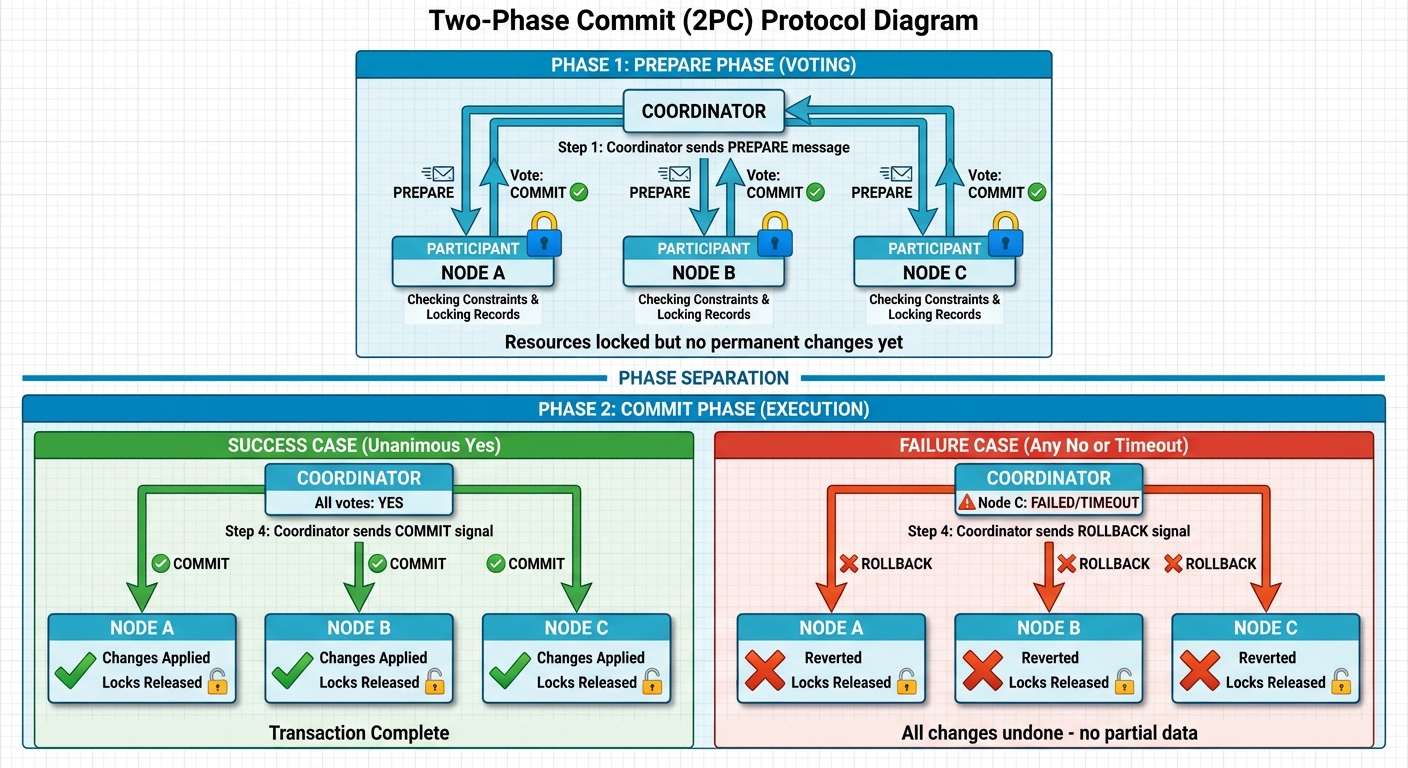

To achieve this, Ignite utilizes a Two-Phase Commit (2PC) protocol. Think of it as a “unanimous vote” system that ensures data remains consistent across multiple nodes, even if some nodes or network links fail.

Phase 1: The Prepare Phase (Voting)

- The transaction coordinator sends a “Prepare” message to all participating nodes.

- Each node checks if it can safely commit the transaction (e.g., checking constraints or resource availability) and locks the necessary records.

- Nodes reply with either a “Vote to Commit” or a “Vote to Abort.”

- At this stage, no permanent changes are made, but the resources are “reserved.”

Phase 2: The Commit Phase (Execution)

- The coordinator collects all votes and makes a final decision:

- Unanimous “Yes”: If every single node voted to commit, the coordinator sends a “Commit” signal. All nodes then make the changes permanent and release their locks.

- Any “No” or Timeout: If even one node fails or votes to abort, the coordinator sends a “Rollback” signal. Every node reverts to the previous state, ensuring no partial data is left behind.

This architectural choice brings distinct trade-offs:

- The Advantage (Atomicity): 2PC ensures that a transaction either succeeds on all participating nodes or fails on all of them. This eliminates the partial-update risks found in simpler replication models, providing the “Gold Standard” for data integrity.

- The Potential Risk (The Blocking Problem): In a standard 2PC implementation, if the Transaction Coordinator fails after the “Prepare” phase but before sending the “Commit” signal, participating nodes are left in a “Heuristic” state. They hold onto locks indefinitely, waiting for a coordinator that may never return. This can lead to system-wide resource exhaustion and deadlocks.

- Ignite’s Solution (Automatic Recovery): To mitigate this, Ignite incorporates a sophisticated Automatic Transaction Recovery mechanism. When a coordinator fails, the remaining primary and backup nodes for the affected data communicate with each other to reconstruct the transaction’s state.

Explicit Lock

This is the most straightforward way to coordinate tasks across a distributed cluster. The parameters allow you to fine-tune the balance between Safety and Performance.

// Initialize or get a distributed lock with specific behaviors

IgniteLock lock = ignite.reentrantLock(

"reportGenerationLock", // Name: Unique identifier for the lock across the cluster

true, // failoverSafe: If the lock owner crashes, release the lock automatically

false, // fair: If false (non-fair), throughput is higher as it skips FIFO queuing

true // create: Create the lock if it doesn't already exist

);

try {

// Attempt to acquire the lock with a timeout to prevent deadlocks

if (lock.tryLock(10, TimeUnit.SECONDS)) {

try {

// Critical Section: Only one node/thread can execute this at a time

System.out.println("Lock acquired! Performing cluster-wide task...");

} finally {

// Ensure the lock is always released

lock.unlock();

}

} else {

System.out.println("Could not acquire lock within 10 seconds. Task skipped.");

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

The key takeaways from the example above are the failoverSafe parameter and the tryLock timeout. Because Ignite is a data-grid-based system rather than a simple utility, it addresses the inherent challenges of distributed environments through the following mechanisms:

- Automatic Release via Node Failure Detection Nodes within an Ignite cluster monitor each other’s status in real-time through heartbeats. You don’t have to worry if a node holding a lock suddenly crashes; as soon as the cluster detects the node’s departure (“Left” state), it automatically releases or rolls back all locks and pending transactions owned by that node. This serves as a critical safeguard against “ghost locks,” much like Zookeeper’s Ephemeral Nodes.

- Implicit & Explicit Timeouts In a distributed environment, network jitter can cause lock acquisition to hang indefinitely. Ignite defends against this by providing explicit timeouts, such as tryLock(10, TimeUnit.SECONDS), allowing developers to prevent deadlocks manually. Furthermore, even if a developer misses this step, Ignite’s internal transaction timeouts and topology change detection kick in to prevent the entire system from grinding to a halt.

- Ownership-based Management Internally, Ignite manages locks as ownership rights over specific data (Keys). This architecture allows the system to maintain strict data consistency across the entire cluster while enabling efficient coordination by involving only the necessary nodes.

Distributed Transactions

One of Ignite’s most powerful advantages is that it doesn’t just provide “locks”—it provides transactional integrity built on top of them. While tools like ZooKeeper are external to your data, Ignite’s locks are deeply integrated with the data grid, allowing for sophisticated optimizations.

Transaction Concurrency Modes: Ignite allows you to choose the locking strategy that best fits your workload contention:

- Pessimistic Locking: This mode acquires locks immediately upon the first read or write operation. Conflicting transactions are blocked until the lock is released. This is the “safe” choice for high-contention scenarios where multiple threads frequently fight for the same record.

- Optimistic Locking: No locks are acquired during the execution phase. Instead, Ignite validates version conflicts only at commit time. This is significantly faster for low-contention workloads as it minimizes the time locks are held.

// Example: Configuring a Pessimistic Transaction

try (Transaction tx = ignite.transactions().txStart(

TransactionConcurrency.PESSIMISTIC,

TransactionIsolation.REPEATABLE_READ)) {

// Lock is acquired here immediately

cache.put("key1", "value1");

cache.put("key2", "value2");

tx.commit(); // Locks released after 2PC completes

}

The “Performance Cheat Codes”: Colocation & 1PC: Standard distributed locks usually require multiple network round-trips (hops). Ignite reduces this overhead through Data Colocation and One-Phase Commit (1PC).

- Data & Lock Colocation By using the @AffinityKeyMapped annotation, you can ensure that a specific lock resides on the exact same physical node as the data it protects. This turns a “Distributed Lock” into a “Local Lock.”

class UserLock {

@AffinityKeyMapped

private String userId; // The lock and the User's data will live on the same node

}

- One-Phase Commit (1PC) Optimization When you colocate your data and logic correctly, Ignite detects that all affected keys reside on a single node. In this scenario, Ignite automatically bypasses the heavy 2-Phase Commit and uses a 1-Phase Commit (1PC).

Standard 2PC: Coordinator ↔ Multiple Nodes (Multiple network hops).

Ignite 1PC: Coordinator (Local) → Single Node (Zero or minimal network hops).

- This combination of Affinity Colocation and 1PC allows Ignite to achieve throughput that is mathematically impossible for centralized systems like ZooKeeper, as it effectively removes the “distributed” penalty from the distributed lock.

Native Object Handling

Ignite handles complex object types natively, not just strings. You can store structured lock metadata without manual serialization. This provides you few advantages.

- Developer Productivity: You can store structured lock metadata—including timestamps, owner IDs, and custom status flags—directly as Java objects. There’s no need to write boilerplate serialization code.

- On-the-Fly Access: Ignite uses a binary format that allows the cluster to read specific fields of your object (like acquiredAt) without de-serializing the entire thing. This keeps the “coordination” part of distributed locking extremely lightweight.

// Define a rich metadata object

public class LockInfo {

private String owner;

private String reason;

private long timestamp;

}

// Store it directly as a value

cache.put("order_lock_123", new LockInfo("Node-A", "Inventory Update", now()));

SQL Support

While Apache Ignite operates as a Key-Value store at its core, it features a robust SQL engine that allows you to treat your data grid like a distributed relational database. Ignite achieves SQL support by maintaining a Distributed SQL Index alongside the raw data.

- Schema Mapping: Every “Cache” in Ignite can be mapped to a “Table.” The “Key” often represents the Primary Key, and the “Value” (often a POJO or Binary Object) represents the columns.

- Distributed Execution: When you run a SQL query, Ignite’s optimizer decomposes the query and sends it to all nodes holding the relevant partitions. Each node executes the query locally against its own memory and sends the results back for final merging.

The real “killer feature” is the integration of SQL with Ignite’s transaction engine. Unlike simple NoSQL stores where SQL is often “eventually consistent,” Ignite allows you to run SQL within an ACID transaction scope.

- Implicit Locking for DML: When you execute an UPDATE or DELETE statement within a transaction, Ignite automatically identifies the impacted keys and acquires the necessary Key-Level Locks using the 2PC protocol we discussed.

- Complex Atomic Changes: You can mix Key-Value API calls and SQL statements in a single transaction. For example, you can use the Key-Value API to fetch a specific lock record and then use SQL to update thousands of related status rows—all as one atomic unit.

try (Transaction tx = ignite.transactions().txStart(PESSIMISTIC, REPEATABLE_READ)) {

// 1. Key-Value API: Lock a specific control record

LockControl ctrl = lockCache.get("maintenance_lock");

// 2. SQL: Update multiple records atomically

String sql = "UPDATE Tasks SET status = 'CANCELLED' WHERE type = 'CLEANUP' AND locked = true";

taskCache.query(new SqlFieldsQuery(sql)).getAll();

// 3. Commit: Both the KV get/lock and SQL update are committed via 2PC

tx.commit();

}

Language-Specific Limitations

While Ignite has clients for Java, .NET, C++, Python, and Node.js, advanced features vary by language:

- Java client is most feature-complete (native implementation)

- .NET has strong support but slightly behind Java

- Python/Node.js clients support basic operations but lack transaction APIs and advanced locking modes

- C++ client is thin, focused on cache operations

If you need full transaction support, you’re effectively locked into Java or .NET. No licensing issues though—Ignite is Apache 2.0 licensed.

Summary

- Much higher operational complexity than Redis. Requires understanding of distributed caching, partition topology, and rebalancing.

- Ignite loads entire datasets into RAM by default. A typical production deployment requires 64GB+ per node. Off-heap storage helps but adds complexity.

- Network chattier than simpler systems. Background tasks (rebalancing, discovery) consume bandwidth.

- Ignite makes sense when you need distributed caching AND locking. For locks alone, it’s massive overkill—you’re deploying a full compute grid for a coordination primitive.

All distributed databases eliminate single points of failure, but require multiple network round-trips for consensus—adding 5-50ms latency compared to single-node systems.

Conceptual Shift: Async Distributed Message Systems

The best lock is no lock at all.

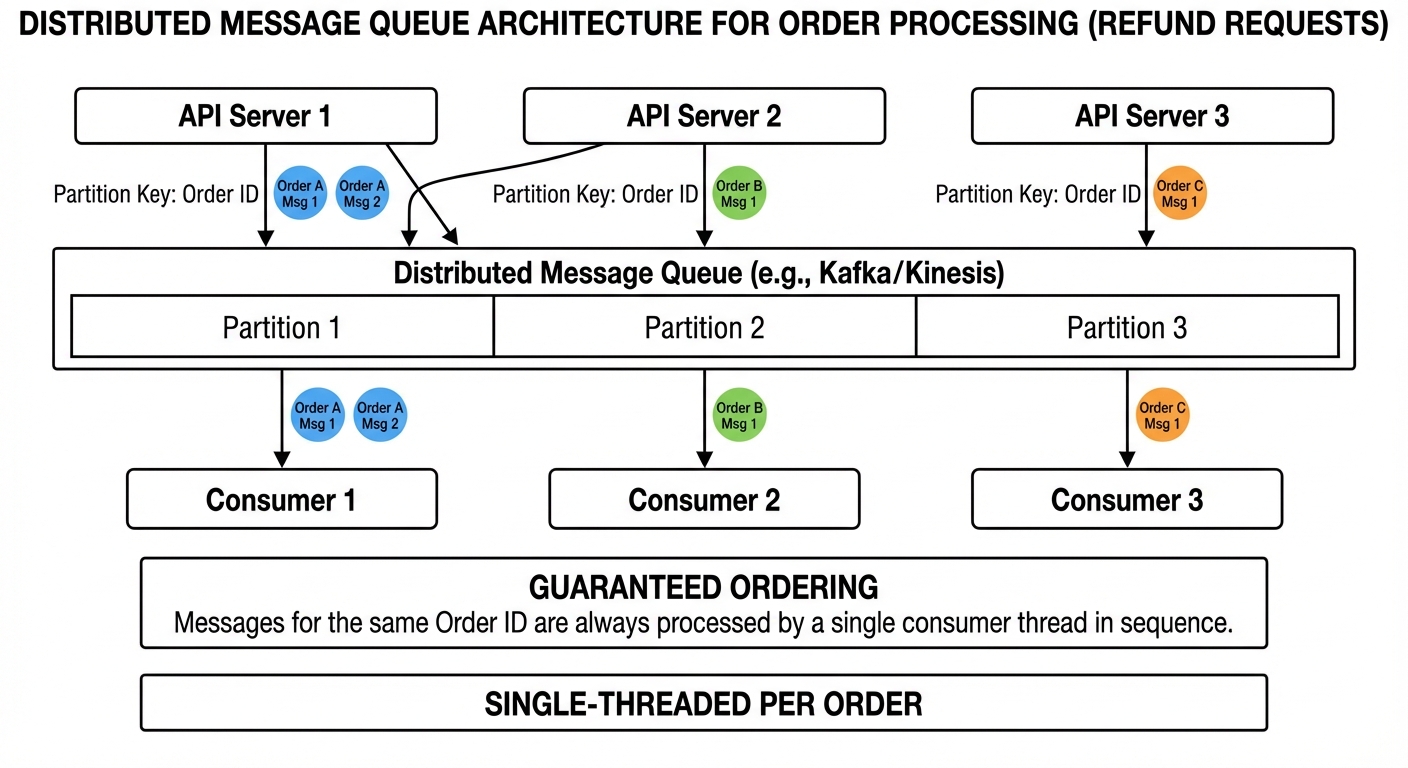

Instead of having multiple services compete for a lock, restructure the problem so race conditions can’t happen. For the refund scenario, publish refund requests to a message queue and process them sequentially—one request per order at a time.

The Partition Key Strategy

Message systems like Kafka, Kinesis, and Google Cloud Pub/Sub support ordering guarantees based on a partition key:

- When publishing a refund request, set the order ID as the partition key

- The message system routes all messages with the same key to the same partition

- Each partition is processed by one consumer at a time (though a single consumer can handle multiple partitions)

- Messages within a partition are processed in order

Your parallelism is capped by partition count. With 10 partitions, you can’t effectively use more than 10 consumer instances for that topic.

All refund requests for order 12345 are routed to the same partition and processed serially. Serialization happens through message ordering rather than locks.

Ultimately, with order guaranteed by the partition key, your only remaining responsibility is to ensure your processing logic is idempotent.

# Publishing side (any API server)

def request_refund(order_id: str, amount: float):

refund_id = generate_unique_id() # Idempotency token

message = {

'refund_id': refund_id,

'order_id': order_id,

'amount': amount,

'timestamp': time.time()

}

# Kafka example - partition key ensures ordering

producer.send(

topic='refund-requests',

key=order_id, # Critical: same order always goes to same partition

value=message

)

return {'status': 'processing', 'refund_id': refund_id}

# Consumer side (separate worker process)

import psycopg2

def process_refund_message(message):

refund_id = message['refund_id']

order_id = message['order_id']

amount = message['amount']

conn = psycopg2.connect("dbname=orders user=app")

try:

with conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

# Atomic idempotency check using unique constraint

# If refund_id already exists, this INSERT fails and we skip processing

try:

cur.execute(

"INSERT INTO processed_refunds (refund_id, order_id, amount, processed_at) "

"VALUES (%s, %s, %s, NOW())",

(refund_id, order_id, amount)

)

except psycopg2.IntegrityError:

# Already processed, skip

conn.rollback()

return

# Validate and update order

cur.execute("SELECT total_amount, refunded_amount FROM orders WHERE id = %s", (order_id,))

order = cur.fetchone()

if order and order[1] + amount <= order[0]:

cur.execute(

"UPDATE orders SET refunded_amount = refunded_amount + %s WHERE id = %s",

(amount, order_id)

)

# Transaction commits automatically on context exit

process_payment_reversal(order_id, amount)

finally:

conn.close()

Critical detail: The processed_refunds table needs a unique constraint on refund_id. The database enforces idempotency atomically—if two consumers process the same message, only one INSERT succeeds.

Technology Choices and Their Differences

Kafka partitions are fixed at topic creation. Each partition in a consumer group is assigned to exactly one consumer; if that consumer crashes, Kafka rebalances and reassigns the partition to another consumer. To increase parallelism, create a new topic with more partitions and migrate consumers. Choose Kafka for strict ordering guarantees when you can handle the operational complexity.

AWS Kinesis allows dynamic shard splitting and merging without downtime. The partition key mechanism is similar, but operational scaling is more flexible. Choose Kinesis if you’re AWS-native and need to adjust throughput without redeployment.

Google Cloud Pub/Sub with ordering keys provides strong ordering guarantees within a region under normal operation. However, ordering can be disrupted during regional failures or extended client disconnections that trigger message reassignment. Avoid Pub/Sub if strict ordering is critical to correctness.

Consistency Model Change

This approach shifts from strong consistency to eventual consistency. With synchronous locking, a refund is immediately visible. With message queues, there’s a processing delay—potentially seconds or minutes.

If your API needs read-your-writes consistency (user checks balance immediately after refund), implement status polling:

# Status endpoint

def get_refund_status(refund_id: str):

result = db.query(

"SELECT status, processed_at FROM processed_refunds WHERE refund_id = %s",

(refund_id,)

)

if result:

return {'status': 'completed', 'processed_at': result[0]}

return {'status': 'processing'}

# Client polls this endpoint after requesting refund

Architecture Impact

Shifting from synchronous locking to asynchronous event-driven flow has significant implications:

Benefits:

- No lock contention or timeout handling

- Built-in backpressure through queue depth

- Easy to add processing steps in pipeline

- Simpler retry logic

Drawbacks:

- Can’t provide immediate response (refund is “processing”)

- Need separate system to track job status

- Request flow spans multiple services

- Consumer lag monitoring becomes critical for operations

When This Doesn’t Work

Message ordering doesn’t replace all distributed lock scenarios:

- Election/leader selection: Need active coordination, not message processing

- Global rate limiting: Requires real-time coordination across services

- Atomic operations across entities: If a refund must atomically update order, user wallet, and merchant balance, single-partition ordering doesn’t help. Solving this requires saga patterns with compensation logic or distributed transactions—both add substantial complexity and are beyond the scope of this comparison.

Message systems work when you can decompose operations into single-entity updates processed asynchronously. If you need synchronous cross-entity transactions or immediate consistency to the user, you still need locks or transactional guarantees.

Conclusion: The Right Tool Mentality

Distributed locking isn’t a single technique—it’s a spectrum of trade-offs. Redis with SET NX EX handles rate limiting and simple coordination at sub-millisecond latencies. PostgreSQL advisory locks provide durability and transactional consistency when you’re already using a relational database. Zookeeper and etcd deliver strong guarantees for cluster coordination. Message queues sidestep locking entirely for event-driven workflows.

The wrong choice costs more than performance. Running Zookeeper for API rate limiting adds operational complexity with no benefit. Using Redis locks for financial transactions risks data loss during failover. Using database locks for high-throughput caching creates bottlenecks.

Match your solution to your constraints:

- Redis: Extremely low latency requirements, acceptable to lose locks during failover, simple coordination

- Distributed databases: Need transactional consistency, already managing database operations, can tolerate moderate latency

- Coordination services (Zookeeper/etcd): Leader election, configuration management, cluster state—when correctness matters more than speed

- Message queues: Event-driven architectures where serialization through queues eliminates lock contention entirely

Operational concerns determine success more than algorithm choice. A perfectly implemented Redlock fails if you don’t monitor lock acquisition times and alert on timeouts exceeding SLAs. Database advisory locks become invisible deadlocks without query timeout tracking. Without observability—lock hold times, acquisition failures, timeout rates—you’re debugging distributed systems blind.

Instrument everything: lock acquisition latency, hold duration, timeout frequency, retry patterns. Set up alerts for abnormal lock durations before they cascade into outages. Test failure scenarios in staging: network partitions, clock drift, process crashes mid-lock.

Choose the simplest solution that meets your reliability requirements, then invest heavily in making it observable. That’s how distributed locking works in production.